PAULETTE: THE AVATAR’S ONE FAMILY

Paulette – The Avatar’s One Family.Pdf

Part One: Sri Aurobindo Ashram

Sri Aurobindo, the Mother, Auroville… Not ordinary gurus leading a few people to salvation, but Avatars heralding a new world and society. Those who belong to the Avatar’s circle take birth with him when a societal upheaval is bound to come – then leave when the momentum is over. In that circle, the psychic being chooses the family and the teachers, the husband or wife and the companions for whom the inner quest goes along with the quest for the ideal society. As in Mother’s New Year message,

“When you are conscious of the whole world at the same time,

then you can become conscious of the Divine.”

Psychic rebirth in a spiritually-nurturing environment

Sri Aurobindo highlights the “religion of humanity” as the highest achievement of the West, and my upbringing was steeped in it – how to redeem the human condition was my generation’s burning quest. I grew up amongst the wealthiest few in Italy, while at the same time confronted with the postwar hopelessness of the many. My story is one of seeking and finding amidst the deep societal transition following the tragedy of World War II. And once found, transitioning to Sri Aurobindo was for me the most natural thing in the world: the Avatar has always been present in my life through those closest to me.

My Italian grandfather was a Futurist painter in the Montmartre bohemia, and also a fairy-tales illustrator and a caricaturist; he was an idealist whose vision of society prepared me for Mother’s Auroville. Spending the summer holidays in the pre-Alps, at dawn I accompanied him to the woods; tears rolled down his cheeks, he whispered, “I don’t believe in Thee, yet I see Thee in every form”.

My French mother, a painter and a musician, choreographed sacred mysteries in arenas with hundreds of dancers. I followed her through castles and cathedrals, bathing in the numinous mysticism of the Middle Ages. My father, a noble from Hungary, was a chemical engineer who consecrated his existence to lab research. An atheist and a mystic, when my mother, “the great priestess of sacred dance”, died at 44 of cancer, he wrote “This sheath of peace and bliss enwrapping my entire being is the radiance of the soul of my wife.”

These are the people who formed me, and along with them were the Marcelline nuns who taught me from age three until I turned fourteen. They had pledged poverty, humility, no ownership; although like their students they hailed from aristocratic and wealthy upper-class families, they slept in a dormitory and ate noodles or cabbage soup every day. If gifted a book, a pen or a plant, at the endof the school-year, the Abbess had to grant them permission to keep them.

Two, who joined at age 26, impressed me the most: one was a noble whose family had offered its wealth to finance Italy’s Independence Wars against the Austro-Hungarian Empire (my Hungarian family did the same); the other had parents who were among the greatest collectors of contemporary art in Italy. At 10, we were the first pupils of a new teacher: she was 20 and still attended the university; she taught us Latin and literature, but she also taught us to evaluate our good and bad actions, every day, before falling asleep. The Mother taught the students the same.

We wore immaculately white uniforms and shoes, and our school was regarded as one of the best in town. Those nuns taught from the kindergarten up to the high school Classics (Greek, Latin, philosophy, history of art, literature – along with sciences); from cleaning to teaching, they did all the work themselves. Profound mystics, those nuns embodied as well the ethical Roman types Sri Aurobindo describes. This was my first experience of a spiritual community – a sangha – where faith translated into self-offering and minimal material needs; the well-being of all humans was central to the teaching. For eleven years I was taught by example, as the Mother expects teachers to do.

My Post-World War II generation

The daily contemplation of wreckage, of a desperate humanity struggling for survival was my passport for Auroville. People were so different, then! Past and present wars and post-war horrors compelled us to be compassionate, humane. My generation was scarred by a wound that cannot heal and yet is a gift, a grace divine. My birthplace too was a psychic choice. The Lake Maggiore, partly in Italy and partly in Switzerland, was a terrestrial paradise famous for its luxuriant parks and villas along the shoreline backed by impervious mountains; but during World War II this enchanted scenery became the theatre of atrocious massacres by the Nazi fascists, and the civilian population embraced the Partisans’ Resistance. In my native village the artist and the architect, the priest and the count, the peasants and the mountaineers grew into one single being fighting for freedom of the motherland.

I grew up in a time and milieu eliciting a strong humanitarian concern, along with a deeply embedded civic consciousness. Living side by side with a dispossessed humanity is ‘the primal wound’ (Arthur Janov’s therapy of ‘the primal scream’) that has accompanied me for life.

This made of us – those who outlived the war tragedy, and those born at the end like me – who we are. We were the heirs of a dying world reborn into the future.

Milan was the first economic and industrial pole and the second largest city of Italy. During World War II, from 1940 to 1945, it was the most bombed city in Northern Italy and at least 2,200 people, particularly the poorest who had no financial resources to flee, were killed. One third of the buildings were destroyed or had to be demolished, leaving at least 400,000 people homeless – over one third of the population; the rubble was used to create an artificial hill. The major industries and the transport system were heavily damaged; the public transport inside the city was completely disrupted. The barbarism of such destruction was described in Wikipedia: “Due to the area bombing focusing on the city centre, the cultural heritage was hit the hardest; three quarters of the historical buildings suffered various extents of damage, including the Cathedral, the Basilica of Sant’Ambrogio, Santa Maria delle Grazie, the Sforza Castle, the Royal Palace, La Scala and the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele.” A bomb fell a few meters’ distance from Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Last Supper’, miraculously saved; we lived a five minute walk from there and from the Castle.

Ruins in shabby fields defacing our elegant neighbourhood in central Milan – Italy’s cultural and economic engine – were our daily sight. So at school we organized fairs, putting on sale precious items from home to support the homeless, whom our nuns fed and clothed. Brotherhood, all for one and one for all, were deeply embedded values that all those I knew and loved had in common. We came of age nurtured by the thirst for equality and justice. Sharing and mercy were our guiding stars.

Was it by chance that the architect and urbanist who coordinated the liaison with the Partisans’ Resistance along the Lake Maggiore was my godfather – who in the Sixties will create the monumental “Park of Memory and Peace” dedicated to those slain during World War II? On the site where 43 partisans were shot, at 3 kms from the village where I was born three months earlier? Was it by chance that my grandfather was his helper?

And was it by chance that, before reaching his Ashram, the only text by Sri Aurobindo that I read, as if it was addressed to my own people, was “The Doctrine of the Passive Resistance” – which in India became an organised resistance as soon as swadeshiand swaraj became the national cry? Hungary and Italy were two of the four “martyr-nations” that Sri Aurobindo salutes.

The savagerie of a war of unprecedented cruelty that threatened the planet stirred people who until then had been indifferent to the fate of the poor and the oppressed. But when no one was secure – when ruin, deportation, torture, and death could be anyone’s fate – then a superhuman force awoke in people, awakening the strength to resist in solidarity with each other, and overcome. On another continent, Sri Aurobindo, glued to the Allies’ radio, fought occult battles for the same cause – and won.

From the Gospel and Existentialism – to Sri Aurobindo and the Mother

The abyss between the privileged world of my schoolmates, versus the desperate reality surrounding us was unbearable. Reading one of my essays, my grandfather commented that I was a communist; “Jesus – the Gospel!” was my astonished reply. So at fourteen I parted from my nuns and schoolmates and joined the public classic high school. A new adventure commenced for me, nurtured by teachers I will never forget (Kireet Joshi said he wished we had had them in Auroville).

I was sixteen when I walked away from my multi-millionaire godmother, of whom I should have been the heiress. Siddhartha shone in many of us. The fathers of three of my new friends were Partisan commanders slain by the Nazi fascists, and their sons carried the torch. The world’s ephemeral glittering was a play of shadows; nothing tamed the feeling of absurd unreality.

Devouring Sartre, Camus, Kafka, I plunged into existentialism. Little I knew that this would be the gateway to Advaita Vedanta, the peak of Indian spirituality: nothing is real, nothing makes sense but the Self. But I was just a teenager daydreaming of a different humanity, having nowhere to turn.

The years at the high school and the university, under my new teachers’ enlightened guidance, were a preparation for the youth revolution in 1968, about which the Mother poignantly commented, in her long dialogue with Satprem: “…There IS a Response. There IS a Force that wants … to express itself.”

At twenty I had a motto: happiness is for all or for no one. My husband, a philosophy graduate, was a director of the cultural programs for Italian television; our friends taught at universities. But the more I grew aware that despite our lofty ideals we were privileged in every sense, the deeper was my pain. Interacting with exponents of the working class, as typical of the cultured youth in the Sixties, made me even more poignantly aware of the abysmal disparities: us versus them. After the ephemeral victories of 1968, the reverie of universal brotherhood was once more shattered. There was no ideal society, there would never be any. The impasse was complete.

Signposts for the wandering pilgrim

In June 1973, in a park, by chance, I ran into my Corporeal Mime teacher, someone who I hadn’t seen for ten years. Out of the blue, he told me that he would introduce me to an actress who just returned from India “enthusiastic”. I sat on a bench, gazing at a large tree, and for two hours I lost consciousness of my surroundings. Three days later I met that young woman in the park of the Royal Villa, Milan, at a rehearsal for the famous theatre director G. Strehler.

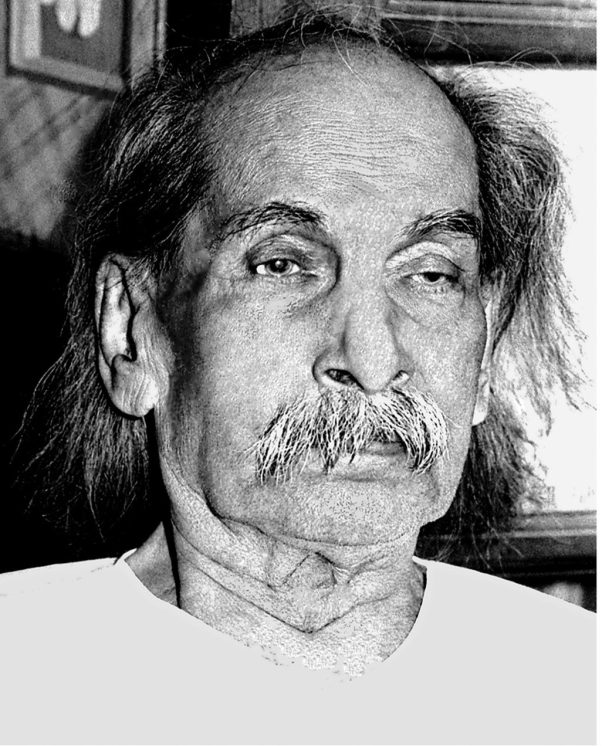

She showed me a small, small photograph by Cartier Bresson of Sri Aurobindo – and I saw God…

Three months later I commenced my pilgrimage, alone, with a backpack and sleeping bag, crossing by bus and by train the Muslim countries. No airplanes would do for my generation in those years – some came overland and others by boat: India was an inner realm to be reached meter by meter, inch by inch.

On October 12th, entering from Pakistan, I knelt and kissed the Indian soil: I had reached “the Promised Land”. This was Mother India for thousands of young travelers refusing “the affluent society” they hailed from (as expounded by Galbraith), refusing the napalm bombs in Vietnam, refusing everything.

On 18th November 1973 I was welcomed at the Sri Aurobindo Centre in Kolkata, and then suddenly I was left alone: the news of Mother leaving the body had come!! Her photo on the stairs, with a message, struck me like lightening: “When you are conscious of the whole world at the same time, then you can become conscious of the Divine.” Her words were an inner command, an adesha, her legacy to me. The ultimate quest had begun and there was no way back. I was 29.

The Samadhi and the Ashram: my home, my people!

When I reached Pondicherry and the Sri Aurobindo Ashram, an Indian girl, Mounnou Bhandari, stood at the gate, as if expecting me. Addressing me in French, she took me to the samadhi where the mortal remains of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother lie. Flowers, incense, white-clad silhouettes whom I saw as angels… I burst into tears, in front of everybody: I had returned home, to my people!

The next day, the girl introduced me to Jiji Kiran Kumari, her auntie. Mounnou had come at three with her parents, a wealthy family from Kolkata; but she refused to leave the Mother and so was confided to her auntie who for twenty-eight years worked at Mother’s personal service, in her room. And daily, Mounnou followed her auntie there. Auntie Jiji had reached the Ashram in the 1930s, at age eighteen. She never left, never saw again her well-off family, never wore again a colored sari, never crossed the canal that separates the Ashram from the noisy old town.

Those were the Ashram’s golden years, sadhana proceeded at full speed. Sri Aurobindo replied to someone that a dozen of his disciples had achieved the cosmic consciousness. The supramental manifestation was imminent until WWII delayed it.

The child sitting on Champaklal’s knees, playing with his beard, was my first new friend; and her auntie was the second. And the other child with the Ashramites – and also sweeping daily to clean around the Samadhi – was my daughter Blanchefleur.

I met Jiji daily and she would unveil minute details of her serving the Mother. Then after tea, I shifted to the late Rishabhchand’s room, typing notes on his typewriter from his manuscript on Sri Aurobindo’s early life. He was Mounnou’s grandfather and Jiji’s brother-in-law. My first research on the Master commenced in that room; my husband and close friends were so taken over by the reading that they wished I had published a book.

A special dispensation by the Ashram Trust allowed me to live with Jiji for three months in the house the Mother had allotted her. Learning that nothing is to be wasted and happiness is non-material, I treasured that experience every day, being one with Her people. Six sadhikas shared the common toilet and bathroom in the courtyard. Minimal living!

The foundations for my research on Integral Yoga were set by scholars and yogis Rischabchand, Nolini Kanta Gupta and Kishor Gandhi … but Jiji Kiran Kumari was my teacher – not in words, but in deeds – showing me unconditional surrender to the Mother.

I spent hours in the hollow of the samadhi’s tree, and no one could dislodge me; I wrote poems and passed into samadhi states, in and out of the body. I was flooded by spiritual experiences, as it often happens with beginners, to open the path.

The twelfth day, walking on Nehru Street, I felt a tremendous force coming down, crushing my skull; then a massive peace descended upon me as drops of dazzling light.

Not meditation – concentration! Integral Yoga is methodic routine concentrated on the Divine, repeating daily the same actions, at the same time, at the presence of the same people, in perpetual self-offering, alone or in a crowd, with no other guru but one’s psychic being.

I wiped dishes at the Dining Room, touched up Mother’s photographs at the Press, cut the faded flowers in the Ashram compound. While walking I collected flowers and grasses for the dried-flower collages I made on marbled hand-made paper, taking up to three days to be completed; as with my poems, the theme was the One, the Two, the Many: I did not know that I was an Advaitin. I lived in bliss. My sadhana proceeded according to the spiritual significance the Mother had given to the flowers. Every flower or tiny grass, every spot on the walls and sidewalks was a source of wonder and delight. The few square metres in a basic Ashram guest house were all I needed. I was blessed.

For six years I returned to Italy every six months, after spending six months at the Ashram, but the last time took me one and half years to return to my husband who lived in the historical centre of Rome. When he told me that, if I chose to remain his wife, I could no longer return to the Ashram, my answer was immediate. Thus ended my thirteen years of marriage with the gentlest, kindest being a woman could dream of for a life partner.

On Mother’s Centenary Day, sitting in the hollow of the samadhi tree next to my Matrimandir co-worker (and future husband), we pledged to consecrate our lives to Integral Yoga and work at the Matrimandir’s construction. In 1985, seven years later, I joined Auroville at last to work at the ‘stars’ on the roof of Matrimandir.

Yoga is “sharp like the razor’s edge” as it is said. The Ashram’s sadhaks, silently teaching by example, had given me the basis, I bathed in a golden dream; but the true ordeal and crucible of alchemical transformation – what turns the being into a tabula rasa, stripped naked of anything one may cling to – is Auroville, the future ideal society of the Avatar.

Unless you are determined to go up to the end, don’t even commence Sri Aurobindo warned. The “Hour of God” is our present.

Paulette,

Auroville, August 2024

Part 2 – “The Avatar’s Auroville” will appear in the November 24th Darshan issue

Quotes from Sri Aurobindo & The Mother about “The Avatar’s Family” and their references are here:

Q: In her book ‘Conversations’ the Mother says: ‘We have all met in previous lives… and have worked through ages for the victory of the Divine.’ [7 April 1929]. Is this true of all people who come and stay here? What about so many who came and went away?

A: Those who went away were also of these and still are of that circle. Temporary checks do not make any difference in the essential truth of the soul’s seeking.

SRI AUROBINDO, “On Himself”, 18-6-1933

“The Mother once told me that when an Avatar descends on earth, He brings with him several followers to do His work.”1 She said indeed: “We have all met in previous lives. Otherwise we would not have come together in this life. We are of one family and have worked through ages for the victory of the Divine and its manifestation upon earth”2 Furthermore: “When the psychic is individualised, it chooses the place and the circumstances that will help it best to accomplish what it comes for during the whole of its earthly existence, and when this is done it departs at will.”3

1 “Sudhir Kumar Sarkar: A Spirit Indomitable” by Mona Sarkar.

2 “Questions and Answers”, 7 April 1929.

3 “Sudhir Kumar Sarkar: A Spirit Indomitable” by Mona Sarkar.